For nearly 30 years, a group of entomologists has been collecting and counting bugs from German nature reserves. Their shock findings threaten to change farming practices across Europe.

The Krefeld Entomological Society and its vast collection of insects are based in a rambling old school building in the provincial German city of Krefeld.

It’s here, at the end of the last century, that entomologist Dr Martin Sorg and his colleagues began an ambitious project. Their goal: to track, measure and record the number of flying insects found in the countryside around their city.

Three decades later, the scientists released their findings.

The results shocked Germany, leading the country to start transforming its farming and land management practices.

Flying blind

Some scientists dream of international glory. Dr Martin Sorg just wishes people would stop calling him when he’s trying to work.

“We never expected to get so many emails and so many questions from around the world,” he sighs.

“Yes, it was problematic for us.”

t’s Saturday afternoon in a quiet corner of north-west Germany and Dr Sorg’s day of collecting insects is once again interrupted by an annoying camera crew, this time from Australia.

It’s been a pattern since October 2017 when he and his colleagues from the Krefeld Entomological Society published their findings on flying insect numbers from 63 nature reserves.

It was a scientific bombshell. Insect numbers had crashed by 75 per cent over 27 years, prompting global headlines of “Insect Armageddon”. Politicians across Europe suddenly faced demands to do something about the crisis. Farmers were blamed for excessive spraying of insecticides.

Dr Sorg appears taken aback by his new-found fame. His shoulder-length grey hair and dishevelled clothing speak of a man more interested in data than appearances. But he’s grateful insect biodiversity is finally being taken seriously.

An estimated 80 per cent of wild plants depend on insects for pollination and 60 per cent of birds rely on insects for food.

“Almost nothing works sustainably without insects,” Dr Martin Sorg said.

It’s unfortunate, he tells me, how few long-term studies like his have been carried out.

“We are practically flying blind.”

The windshield phenomenon

For decades, people have sensed something strange was happening in the insect world.

Motorists in Europe and North America noticed seeing fewer bugs smashed on their windshields — a talking point that gained its own Wikipedia entry.

PHOTO: Motorists in Europe and North America noticed seeing fewer bugs smashed on their windshields (Foreign Correspondent: Tomás Ybarra)

PHOTO: Motorists in Europe and North America noticed seeing fewer bugs smashed on their windshields (Foreign Correspondent: Tomás Ybarra)But in a world of scarce research grants, few scientists were prepared to divert resources to the insanely time-consuming task of measuring insect populations over decades.

Dr Sorg and his colleagues were different. In 1989, they decided to launch a comprehensive survey across Germany. It would become their life’s work.

Year after year, from spring to early autumn, the men drove to nature reserves to set up Malaise traps; large tent-like structures that funnel insects up to a brightly lit high point where they’re trapped in alcohol.

The traps were placed in identical locations and each sample was drained, weighed and sorted in a precisely standardised way to ensure a true comparison.

Their findings — built over three decades — are definitive proof of the collapse in insect numbers and have stark implications for the future of commercial farming.

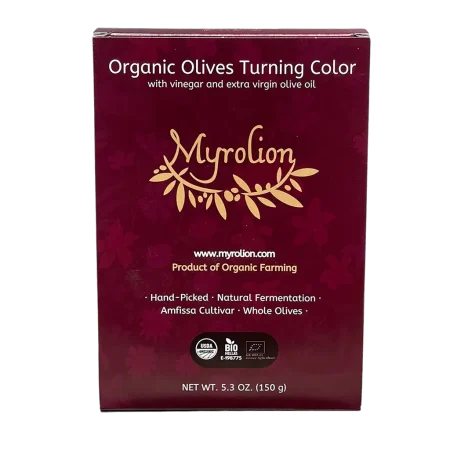

PHOTO: Martin Sorg and his colleagues from the Krefeld Entomological Society. (Foreign Correspondent: Tomás Ybarra)

PHOTO: Martin Sorg and his colleagues from the Krefeld Entomological Society. (Foreign Correspondent: Tomás Ybarra)‘Bucketloads of chemicals’

The nature reserves where Dr Sorg’s team collected their data were close to farms that typically used high quantities of insecticide, including a particularly potent form of pesticide called neonicotinoids.

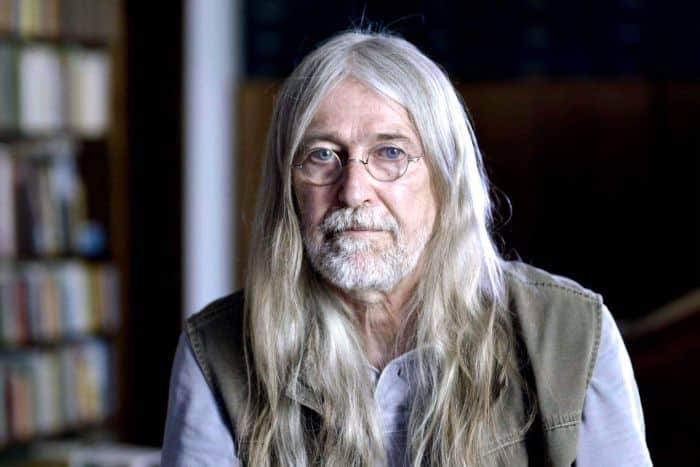

British biology professor Dave Goulson reviewed the project’s data and was a co-author of the final report. He sees these findings as symptomatic of what modern farming practices are doing across Europe.

“The whole system of having food production, a way of farming, which is entirely reliant on chucking on bucket-loads of chemicals is not sustainable,” Professor Goulson said.

PHOTO: Professor Dave Goulson in his garden in Sussex, England (Foreign Correspondent: Tomás Ybarra)

PHOTO: Professor Dave Goulson in his garden in Sussex, England (Foreign Correspondent: Tomás Ybarra)“We are going to wipe out insect life if we carry on this way.”

Professor Goulson believes the world has forgotten the lessons of the 1960s, when the pesticide DDT was banned after it was shown to be killing more species than was necessary and contaminating our food chain.

“We banned a whole bunch of pesticides — but then we introduced new ones to replace them, many of which then eventually we banned,” he says as he shows me around his lush garden in Sussex, southern England.

“So we introduced even more, including neonicotinoids, and 20 years into their use, we’re starting to realise that they too are harming the environment.”

Saving the bees

Many environmentalists agree, and the Krefeld study has prompted German environmentalists to campaign for the use of fewer chemicals in farming.

In February this year, green groups in the southern German state of Bavaria launched a petition demanding government action.

It was called Save the Bees, focussing on the risk to everyone’s favourite pollinator, though petition organiser Norbert Schäffer admits the campaign’s name was more marketing than science.

“It’s of course not just about honey bees”, he said. “It’s about insects. It’s about biodiversity as a whole.”

The streets of Munich were filled with campaigners dressed as bees urging Bavaria’s 9 million registered voters to come out in freezing weather to sign the petition. And 1.75 million people did, making it the most successful petition in Bavarian history.

PHOTO: The “Save the Bees” protest in Munich, which used bees for marketing but was about biodiversity as a whole. (Supplied: Andreas Abstreiter)

PHOTO: The “Save the Bees” protest in Munich, which used bees for marketing but was about biodiversity as a whole. (Supplied: Andreas Abstreiter)The government promised to put their demands into law, including mandating 30 per cent of farmland to become organic by 2030.

“It is a target,” Norbert Schäffer said.

“No one will be forced to go organic. The government has to deliver certain targets, and all the government has to put offers on the table.”

But many farmers are worried, and fear they will be told to stop using pesticides without adequate compensation.

Two hours from Munich I meet Franz Lehner as he is spraying nitrogen fertiliser on his wheat field.

“You can’t prescribe organic farming. The market has to do that,” says Lehner.

“If 30 per cent of our people want organic products to be produced, then 30 per cent of people also have to buy these products. And maybe a maximum of 10 or 20 per cent are really willing to pay more.”

PHOTO: German wheat farmer Franz Lehner says pesticides are essential to feed the world. (Foreign Correspondent: Tomás Ybarra)

PHOTO: German wheat farmer Franz Lehner says pesticides are essential to feed the world. (Foreign Correspondent: Tomás Ybarra)Lehner says that without pesticides, it will be hard to grow enough food for the world’s growing population.

“We have 8 billion people on earth. Without fertilisation, it is not possible to feed these people.”

Despite farmers’ concerns, the idea is spreading. The German state of Baden-Württemburg is planning to hold a similar referendum, calling for 50 per cent organic farming by 2035 and a halving of pesticide-contaminated areas by 2025.

In 2018, the European Union issued a total near-ban on neonicotinoids, despite manufacturers’ assurances it was safe if used as directed. France also restricted the use of pesticides in some urban areas.

“Paris from now on, I bet you will still look just as beautiful,” Professor Dave Goulson said. “All the parks and everything. They’re not going to be overrun with dandelions and cockroaches.”

‘If they go, we go’

Scientists have questioned the notion of an insect apocalypse based on this single German study and many scientists are cautious.

They simply don’t know how insect numbers are faring across the world.

Enter the citizen scientists.

On a Tuesday evening in a patch of forest in the Netherlands a group of retired entomologists and amateur naturalists are trying to fill the gaps.

It’s a busy night of collecting beetles, moths and caddisflies, all of which fly into a makeshift screen.

PHOTO: Retired entomologist Paul van Wielink has found insect numbers have dropped off by as much as 60 to 70 per cent since 1997. (Foreign Correspondent: Tomás Ybarra)

PHOTO: Retired entomologist Paul van Wielink has found insect numbers have dropped off by as much as 60 to 70 per cent since 1997. (Foreign Correspondent: Tomás Ybarra)The atmosphere here is more social than scientific, and some good Dutch beer is cooling for when the collecting’s done. But it’s vital work to understand what’s happening to the insect populations. As in Germany, the news in the Netherlands is bad.

Our host Paul van Wielink tells us the numbers of insects they’ve been collecting since 1997 have dropped off by as much as 60 to 70 per cent.

“We are not going to be long on this earth if it keeps going on.” Paul van Wielink

Van Wielink issues a stark warning about the consequences of insect decline.

PHOTO: Every Tuesday the men collect and count beetles, moths and caddisflies which are attracted to a lit screen.

PHOTO: Every Tuesday the men collect and count beetles, moths and caddisflies which are attracted to a lit screen.(Foreign Correspondent: Tomás Ybarra)

“We are completely dependent on insects,” he said.

“Not only for food, all the dung and carrion is cleaned out by beetles and insects. If they go, we go.”

Fighting extinction

In Australia, there haven’t been enough long-term studies to measure the state of insect populations here.

But German-style protests have already begun. Last week, activists from Extinction Rebellion staged a “Bee-Mergency” in Sydney’s Hyde Park, playing dead while dressed as bees. Six people were arrested.

Extinction Rebellion’s campaign is focussing on the perils of climate change, but it’s unclear what role global warming is playing with insect biodiversity.

The Krefeld study ruled out changes to weather as a cause of insect collapse. And rising temperatures could potentially be beneficial for some insects, particularly in species we’d rather see less of (hello cockroaches and mosquitos!)

The threat is perhaps another symptom of what’s creating climate change: humanity’s ever-increasing exploitation of the environment.

As with climate change, the cost of changing our ways could be enormous, but the cost of doing nothing could be greater still.